New Episode of "Old Pilot Tips" is Available

The latest episode of our "Old Pilot Tips" series sponsored by Avemco is now available. Episode 23 provides reminders on how to exit the runway safely after landing in just 46-seconds. Click here to view it on YouTube.

Featured Course

There are multiple instances of runway excursions daily in the U.S. "Many Happy Returns" will examine the common causes of runway excursions and offer some ways to help avoid them. Valid for 1 credit Advanced Knowledge-2 in the Wings program. Click here to visit the free course sponsored by Avemco.

Pilots and Herbal Supplements

Many of you have completed my "Terrible Triad of Fatigue, Stress, and Medications" course. Some additional information on the potential dangers of herbal supplements is presented in the latest FAA "Pilot Minute" video series. Click here to view the video.

Aviation Physiology Guide

The FAA has a very comprehensive document that clearly explains the many things that can affect the human body during flight. It contains much valuable information whether you are flying a Cub or B-777. Click here for a free download.

More on the Aging Pilots Project

As promised, I will begin hosting limited attendance events to discuss cognitive skills as they relate to pilots. Rather than do a large webinar which is mostly one-way with me doing all the talking, I think this subject is best done informally, with me do a presentation, but including active participation among attendees. The first of these sessions will be on Thursday, September 12 at 8:00 PM Eastern time. Wings credit will be available to those attendees who want it. To earn the Wings credit, completion of an online quiz following the event will be necessary. The event will be on the Zoom Meetings platform and advance registration is required. Click here to register. Meanwhile, I am routinely posting cognitive skills information on my Facebook page. I would suggest following my page for complete information.

Tow Bar vs. Prop

there have been at least two incidents in the past month of pilots failing to remove and stow the tow bar before beginning to taxi. When the tow bar and the prop mix it up, the tow bar will win every time. Prop damage will likely require an engine tear down to inspect for damage. This simple mistake will result in tens of thousands of dollars in damage and an extended down time for the airplane. To help avoid that, click here to check our our "Old Pilot Tips" less than one-minute video on the subject.

Planning an Aviation Event?

If you have an upcoming event and would like to have me deliver one of my presentations, please contact me at gene@genebenon.com. There is no cost for virtual presentations. Please contact me to discuss live, on-site presentations. Click here to download my current presentation catalog.

For the next several issues of vectors, we will replace the "NASA Callback" feature with a series of articles regarding cognitive decline and what science now tells us about how to combat it. We will make frequent references to pilots, but the information applies to everyone.

That Ounce of Prevention

I ended last month’s post with the statement, “As my grandmother told me many times, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” Before we dive into specific cognitive skills. I want to expand on prevention of decline in our skills. It is never too early or too late to begin a regimen of prevention. If twenty-five-year-olds take appropriate steps now to reduce decline, they may reap significant rewards from their efforts as they pass through age 60 and beyond. Even people with noticeable indications of cognitive decline can help to slow the rate of decline and possibly even reverse some of the decline.

The two most important things that can be done, in addition to taking steps to avoid head injury, are to get aerobic exercise on a regular basis and to routinely have adequate sleep.

The science is clear. The brain needs lots of oxygen which of course is delivered by blood flow. Aerobic exercise increases blood flow and therefore oxygen, to all organs, including the brain. Twenty to thirty minutes of aerobic exercise at least four days per week is recommended. The caveat here is that before beginning any exercise program, it is best to check with your doctor to make sure it is okay.

Sleep is important because that is when the toxins are purged from the brain. During sleep, toxins are removed by the glymphatic system which is the brain’s waste elimination system. Most adults need at least seven hours of sleep per night, but that can vary from person to person. Unfortunately, some people suffer from a sleep disorder to some degree. Sleep aid medications, both OTC and prescriptions, often present undesirable side effects and should generally be avoided if possible. Before resorting to medications, check out natural methods of inducing sleep without meds. Just do an internet search for “tips for falling asleep faster” or something similar. Pick a few that might work for you and give them a try.

For a jump start on cognitive skills, check out my Facebook page where I have been posting info on the various cognitive skills almost daily

Stalls - Still Killing Us

The word “stall” is quite versatile. It can be a noun, an adjective, or a verb. As a noun, it can be a horse stall, a bathroom stall, a delaying tactic, or an aerodynamic stall. As an adjective, it can, with the addition of a suffix, be a stalled warm front or a stalled car. Without the suffix it can describe a warning such as a stall warning. As a verb, it can describe an action such as “stall the IRS agent,” or stall the “airplane.”

Obviously, the word predates aviation, but once human flight began, “aerodynamic stall” quickly entered the jargon. The Wright Brothers, Glenn Curtis, Donald Douglas, Charles Lindbergh, Chuck Yeager, and Neil Armstrong all knew and understood the aerodynamic stall. Wolfgang Langewiesche’s timeless “Stick and Rudder,” with an original copyright date of 1944, discusses the aerodynamic stall and how it is caused by exceeding the critical angle of attack on page one of chapter 1. In fact, page 2 includes the quote, “If you only had two hours to explain the airplane to a student pilot, this is what you would have to explain.” Every training course and book ever produced for beginning pilots discusses the aerodynamic stall and angle of attack in detail. It is difficult to imagine any flight instructor not thoroughly training a student pilot on the aerodynamic stall, its relationship to angle of attack, and leading the student through a rigorous program to experience a variety of stalls, stall avoidance, and recovery. The same goes for an instructor conducting a flight review or checkout in make and model new to the pilot.

Yet here we are in 2024 and people are still dying and being seriously injured because a pilot unintentionally entered an aerodynamic stall and did not recover control before the airplane returned to earth in a spectacular fashion. What did those pilots not understand regarding the aerodynamic stall? Was their initial training lacking? Did they not receive competent, adequate recurrent training? Did they not participate in recurrent training? Or did some of those pilots understand the aerodynamics, but proceeded into dangerous situations due to hazardous attitudes or external factors negatively influencing aeronautical decision making?

Professions that can potentially involve life threatening activities such as police, firefighting, and others, incorporate frequent refresher training on the high-risk activities that can be encountered. The training includes ways to mitigate the risks to increase safety. This includes methods to avoid the life-threatening situation whenever possible and how to best deal with it if it presents itself. For example, police officers are trained on ways to de-escalate a conflict but are also trained on how to use tasers and firearms if necessary.

The unintentional aerodynamic stall is a life-threatening event for a pilot. It is often the defining event that ends with a loss of control inflight (LOC-I) and a resulting crash, likely fatal. So, let’s start mitigating that risk, or “de-escalating” right now. An excellent refresher can be found in Chapter 5 of the FAA’s Pilots’ Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (PHAK). More specifically, the discussion of stalls begins on Page 5-22. The latest version of the PHAK can be downloaded in PDF format for free. The entire handbook or individual chapters can be selected by clicking here.

The next step in our mitigating or “de-escalating” is to continue a more detailed discussion of stalls as an integral part of “upsets.” This can be found in Chapter 5 of the FAA’s Airplane Flying Handbook which is also available for free download by clicking here.

Chapter 5 of the Airplane Flying Handbook also begins to address “weapons” to use if our de-escalation efforts fail. That chapter briefly addresses Upset and Recovery Training (UPTR) so let me give my thoughts on that. I believe that any training makes a pilot better. Realistically I know that many if not most pilots have limited budgets and limited time available. I am not convinced that the cost and time spent on some of the UPRT programs offered is the best use of limited resources. Rather than expend the training budget on one extensive UPRT course, I would rather see the pilot spend the time and money on a few flights with a competent flight instructor exploring the edges of the flight envelope, experiencing cross-control stalls, unusual attitude recoveries (both with outside references and with a view limiting device), deep stalls, slow flight, with and without flaps, slips, skids, etc. And, importantly, all this being done in an airplane or airplanes as similar as possible to what the pilot usually flies. We want to build muscle memory in an airplane with the same power response, aileron authority, and rudder authority as the airplane we are most likely to encounter our life-threatening event.

Please don’t dismiss this and allow illusory superiority or optimism bias to let you believe that an inadvertent stall cannot happen to you. It has happened to beginners with basic certification and to experienced pilots with thousands of flight hours and advanced ratings. For the sake of yourself and your family, please take steps to reduce the likelihood that you will fall victim to the inadvertent stall and its resulting consequences.

Accidents discussed in this section are presented in the hope that pilots can learn from the misfortune of others and perhaps avoid an accident. It is easy to read an accident report and dismiss the cause as carelessness or as a dumb mistake. But let's remember that the accident pilot did not get up in the morning and say, "Gee, I think I'll go have an accident today." Nearly all pilots believe that they are safe. Honest introspection frequently reveals that on some occasion, we might have traveled down that same accident path.

A recently retired Navy Lieutenant Commander, age 56, and his 27-year-old passenger died in the crash of a Mooney M20J in Florida the day after Christmas 2021. The pilot held a Private Pilot Certificate and instrument rating and had an estimated 442 hours flight time in all aircraft. He also held a current Class 2 Medical Certificate. His logbook was not recovered so no information on his flight review status is available.

NTSB Photo

The NTSB Report includes the following, "The pilot departed on a local 20-minute flight before returning to the airport traffic pattern. After performing a low approach to the runway, the airplane began to climb slowly from an altitude of about 50-100 ft. While over the runway, just as the landing gear were raised, the baggage door fully opened. A witness reported that after the door opened, the airplane stopped climbing and began a slight turn to the right. Another witness reported that as the airplane was at an altitude of 200-400 ft, along the runway extended centerline, the right wing “dropped” and the airplane appeared to enter a spin, which continued until it impacted the ground. The airplane came to rest upright in a field, with no debris path or ground scars in the vicinity of the wreckage. It was partially consumed by a postcrash fire. Examination of the airplane revealed no preimpact anomalies that would have precluded normal operation."

NTSB Photo.

The NTSB report continues, "The witness descriptions as well as the lack of any lateral debris path or ground scars at the accident site were consistent with an aerodynamic stall/spin. Automatic dependent surveillance – broadcast (ADS-B) data indicated that as the airplane overflew the runway, its groundspeed varied between about 50 and 56 knots. The reported wind at the time of the accident was a headwind of 8-9 knots. These speeds are close to the airplane’s published stall speeds, which vary from about 55 to 63 knots, depending on flap and landing gear configuration. Based on this information, it is likely that the opening of the baggage door startled and/or distracted the pilot, drawing his attention away from maintaining the airspeed. The airplane then likely slowed, which led to a stall and subsequent spin."

NTSB Graphic

The NTSB report also includes this, "Toxicology results identified low levels of both amphetamine and diphenhydramine in the pilot’s cavity blood. The reason for the pilot’s use of amphetamine could not be determined from the available information; personal health records could not be obtained. Thus, whether he was at increased risk for distraction from an underlying attention deficit disorder is unknown and any effects from such a condition could not be determined. Given the low level of diphenhydramine in postmortem cavity blood, it is unlikely that any effects from his use of diphenhydramine contributed to the accident."

NTSB Photo

A crash following the unexpected opening of a door is unfortunately a recurring theme. In this case, the pilot apparently allowed the airspeed to deteriorate and an inadvertent stall, followed by a spin entry occurred. This seems a bit strange since the offending door was a baggage door, clearly inaccessible to a pilot or front seat passenger. The NTSB raises the question of why the pilot had amphetamine in his system and was it a treatment for ADHD. Certainly, distractions and ADHD do not play well together. It is unfortunate that the pilot's personal medical records were not available.

But with all that being said, we must condition ourselves to fly the airplane regardless of what else is happening and by all means avoid the inadvertent stall. One good way to install that practice in our brain is to engage in some simulator training with a CFI or an experienced pilot. Run through emergencies, especially those that may illicit a startle response. Get in the habit of stating out loud, "Fly the airplane!" at the beginning of each event. If that training is done several times and repeated quarterly, there is a good chance that you will follow your own direction if the real thing happens.

Click here to download the accident report from the NTSB website.

Accidents discussed in this section are presented in the hope that pilots can learn from the misfortune of others and perhaps avoid an accident. It is easy to read an accident report and dismiss the cause as carelessness or as a dumb mistake. But let's remember that the accident pilot did not get up in the morning and say, "Gee, I think I'll go have an accident today." Nearly all pilots believe that they are safe. Honest introspection frequently reveals that on some occasion, we might have traveled down that same accident path.

Beyond the news stories, many tragedies are devastating to families. Airplane crashes are certainly no exception to that. A 28-year-old private and his 57-year-old father died in the crash of a Vans RV6 in Virginia in June 2023.

Actual Airplane (FlightAware)

The NTSB report states, "The pilot and passenger were flying back to their home airport after an overnight stay with some friends. A witness, and friend of the pilot and passenger, stated he watched the airplane as it made two circles around his house. On the second circle, he noticed the airplane was in a very steep bank angle and making a tight circle about 100 ft above the ground. He then noticed the nose of the airplane drop down and the airplane impact the ground in a near-vertical attitude. He stated the engine was running well the entire time."

NTSB Photo

The NTSB report continues, "Postaccident examination of the airframe and engine revealed no evidence of preimpact mechanical malfunctions or failures that would have precluded normal operation. Thus, it is likely that while performing the low altitude circling maneuver, the pilot maintained insufficient airspeed and banked too steeply, which resulted in an exceedance of the airplane's critical angle of attack and a subsequent aerodynamic stall."

NTSB Photo

The NTSB probable cause states, "The pilot’s failure to maintain adequate airspeed while maneuvering at low altitude, which resulted in an exceedance of the airplane’s critical angle of attack and a subsequent aerodynamic stall."

NTSB Photo

The pilot had 355 hours total flight time. He had a current medical certificate and flight review. Once again, the inadvertent stall takes its toll. Making steep turns at low altitude is never a good idea. It is too easy to become focused on a ground object and tighten the turn to keep it in view. Perhaps if this pilot had engaged in some training to explore the edges of the flight envelope, he might have been more aware of the stall characteristics of this particular airplane. He likely would have benefited from doing this maneuver at 5,000 feet AGL with a competent CFI skilled in upset and spin avoidance and recovery.

Click here to download the accident report from the NTSB website.

Accidents discussed in this section are presented in the hope that pilots can learn from the misfortune of others and perhaps avoid an accident. It is easy to read an accident report and dismiss the cause as carelessness or as a dumb mistake. But let's remember that the accident pilot did not get up in the morning and say, "Gee, I think I'll go have an accident today." Nearly all pilots believe that they are safe. Honest introspection frequently reveals that on some occasion, we might have traveled down that same accident path.

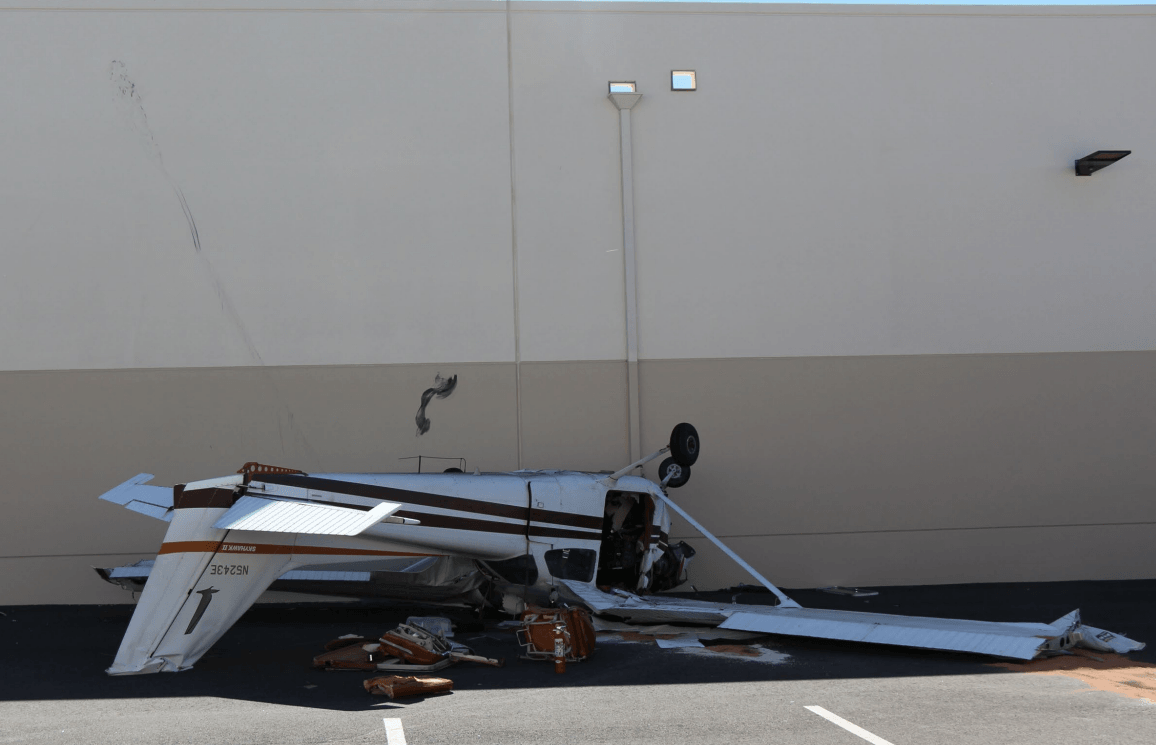

NTSB Photo

Like I have written many times before, many crashes are devastating to families. This crash of a Cessna 172N in California took the life of a-39 year-old newly certificated private pilot and caused serious injury to his three sons. This was the pilot's first flight after passing his practical test.

The NTSB accident report includes the following: "The pilot was taking his family for scenic flights after receiving his private pilot certificate about 2 weeks earlier. They completed one successful flight and then departed on the second, which was the accident flight. Upon returning to their departure airport, the airplane landed normally, but during the landing roll, the front seat passenger heard a “pop” sound and subsequently felt the airplane shake, at which time the pilot started to panic. The pilot advanced the throttle and the airplane lifted off the runway surface again. Surveillance video captured the airplane as it began to climb in a nose-high attitude, drifted left of the runway, then rolled inverted and rapidly descended."

The NTSB report continues, "Postaccident examination of the airplane and engine revealed no preimpact mechanical anomalies that would have precluded normal operation. The wing flaps were found in the retracted position. The source of the “pop” sound reported by the passenger could not be determined, nor could it be determined why the pilot chose to take off immediately after having successfully touched down on the runway, as he had planned a full-stop landing. The reported wind at the time of the accident indicated a headwind accompanied by a right crosswind that was within the airplane’s maximum demonstrated crosswind component.

The circumstances of the accident are consistent with the pilot’s exceedance of the airplane’s critical angle of attack during takeoff, which resulted in an aerodynamic stall and loss of control. Evidence shows that the pilot retracted the flaps from the fully extended position to the flaps up position while the airplane was in a high angle of attack as it veered left of the runway towards buildings. The sudden retraction of flaps at a low altitude would have resulted in a loss of lift and a descent, which likely contributed to the loss of control."

The NTSB probable cause states, "The pilot’s exceedance of the airplane’s critical angle of attack during takeoff, which resulted in an aerodynamic stall and loss of control. Contributing to the loss of control was the pilot’s sudden retraction of the flaps."

French Valley Airport (Google Earth)

What went wrong here? The NTSB report includes this report from the pilot's flight instructor, "One of the pilot’s instructors reported that the pilot had trouble advancing the yoke to keep the airplane’s nose down during go-arounds. The instructor reported that the pilot had a habit of configuring the airplane with excessive nose-up trim for landing." If the pilot had reverted to this practice, it might explain the nose-high attitude observed in the surveillance video. The flap retraction while in the nose-high attitude might be attributed to a rookie mistake or to a lack of sufficient training in go-arounds. We do not know what this pilot's training consisted of, but I recommend that instructors demonstrate the effect of flap retraction at a high angle of attack, but of course do that at a safe altitude.

Click here to download the accident report from the NTSB website.

Not subscribed to Vectors for Safety yet? Click here to subscribe for free!