Syracuse Safety Stand Down Sept. 6th!

The Syracuse Safety Stand Down will be held Saturday, September 6, 2025. Free parking at KSYR, earn three WINGS credits, and enjoy a free lunch courtesy of SAFE. There will be door prizes and SWAG courtesy of Avemco Insurance. I will be there for the entire day and will be doing one presentation. Stop by and say Hi!. Click here for more info from the FAASafety.gov site.

Recommended Video

It is a rare day when the Aviation Safety Information Analysis and Sharing (ASIAS) report does not include at least one mishap on a taxiway or ramp resulting in damage to an aircraft. For each event that is reported, there are likely several that go unreported. Collectively, these mishaps account for many thousands of dollars in damage and considerable aircraft down time. More importantly, many have the potential for serious personal injury or loss of life. Nearly all these mishaps could have been easily avoided. Click here to check out our thirteen-minute "Taxi and Ground Ops" video sponsored by Avemco on YouTube.

Another New Edition of "Old Pilot Tips" is Available

Episode #34 in our series reminds us the the importance of the passenger briefing and provides some thoughts on some essential items. This shorts video is just 43 seconds long. The video is sponsored by Avemco and is narrated by Gene Benson. Click here to check out "Passenger Briefings."

How We Assess Risk: Teamwork Within Our Brain

Risk assessment is a core survival function, deeply embedded in the architecture of the human brain. Long before modern safety systems, our ancestors relied on instinctive and cognitive processes to gauge danger and make life-or-death decisions. Today, those same mechanisms shape everything from daily choices to high-stakes emergencies.

Critical to this system is the amygdala, an almond-shaped structure that rapidly detects threats. It triggers emotional responses—like fear or anxiety—that serve as early warning signals. If the situation is deemed urgent, the brain activates the hypothalamus, launching the "fight-or-flight" response to prepare the body for immediate action.

Meanwhile, the prefrontal cortex—our logical, decision-making center—steps in to evaluate risk with nuance. It weighs options, anticipates outcomes, and incorporates memories of past experiences. This balancing act between instinct and reason is what makes human risk assessment so dynamic. For example, a pilot navigating a thunderstorm may feel an initial emotional surge but ultimately rely on training, pattern recognition, and logic to guide choices.

But, in aviation, pilots should be proactive about identifying potential risks and taking steps to mitigate them. Gene’s Blog this month discusses how we can assess potential risk to avoid the need for the amygdala to get involved.

Risk Assessment - Pre-empting the Amygdala

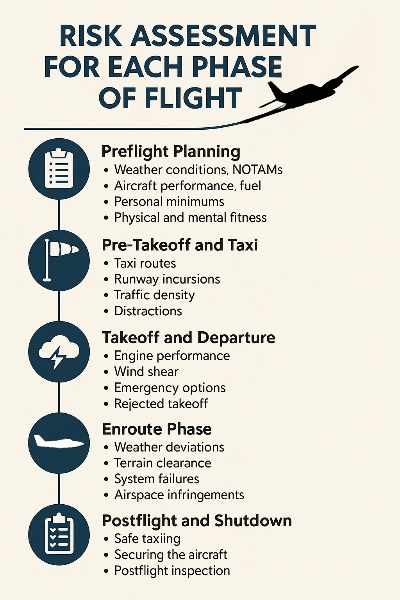

Our cognitive science article this month discusses the human brain's mechanism for assessing risk and taking action against threats. That process should be considered a last resort for pilots. A full-blown emergency may have developed by the time our automatic systems recognize a threat. By breaking down a flight into phases it becomes easier to assess the potential risks in each phase.

The graphic above is not a complete list but provides a framework for assessing risk. In medicine, the team in the OR takes a pause before making the first incision to verify they have the correct patient and are clear about the procedure to be performed, and other critical information. I like to follow that model for a flight. Just before going out to the airplane, a review of the plan for the flight and any significant known risks seems to get my brain focused. Maybe hotspots on the airport pose a risk during taxi, a procedure for terrain clearance poses a risk on departure, or forecast turbulence along the route poses a risk of passenger airsickness.

Then I like to acknowledge and assess the risks and form strategies before beginning critical operations. Before taking the active runway I like to I acknowledge the risk of an engine failure at a low latitude and assess the terrain off the departure end of the runway. What hazards would interfere with landing straight ahead? Within range of a non-towered destination airport I like to form a mental picture of the pattern and assess risks based on based on airport layout, prevailing wind, active runway, traffic on the CTAF, etc. You get the idea. Just stay a step ahead and think about upcoming potential risks.

We can extend this practice beyond our flying into other activities such as driving a vehicle, using power tools, and anything else that poses potential risk.

Let's keep the amygdala and its associates quiet and content to the extent possible.

Accidents discussed in this section are presented in the hope that pilots can learn from the misfortune of others and perhaps avoid an accident. It is easy to read an accident report and dismiss the cause as carelessness or as a dumb mistake. But let's remember that the accident pilot did not get up in the morning and say, "Gee, I think I'll go have an accident today." Nearly all pilots believe that they are safe. Honest introspection frequently reveals that on some occasion, we might have traveled down that same accident path.

This crash happened in California in October 2023. The 54-year-old 20,000 hour ATP and his passenger died in the crash of the Beech A36 Bonanza. The NTSB accident report begins: "The pilot and passenger departed from their home in Utah to a coastal airport in Northern California. After a 4 hour and 11-minute flight, the airplane arrived at the intended destination, but did not descend and subsequently turned inland, possibly due to the presence of cloud cover at the destination. The airplane landed and the pilot obtained about 90 gallons of fuel at an airport about 40 nautical miles southeast of the intended destination. The accident occurred during the subsequent departure from runway 28."

NTSB Graphic

The NTSB report continues, "A witness reported that the airplane lifted off near the end of the 3,670-ft-long runway, clearing trees by about 20 ft before it began a left turn that progressed into a steep turn with an estimated 70-80° bank angle. The witness then noted that, "as it was banking, it started coming lower," and that when the airplane started to bank, 'it lost a lot of altitude from that [the start of the bank] to when it hit the mountain.”

Round Valley Airport 009 (Google Earth)

The NTSB report continues: "The wreckage was mostly consumed by postcrash fire. Although another witness reported hearing a “popping” sound from the airplane, postaccident examination of the airplane and engine revealed no preimpact mechanical anomalies that would have precluded normal operation. Performance calculations indicated that the airplane would have required a takeoff ground roll distance of about 2,600 ft based on its loading and the atmospheric conditions about the time of the accident. It could not be determined whether the pilot initiated the takeoff from the beginning of the runway and used substantially more runway than that predicted by performance calculations, or if the pilot may have initiated the takeoff from the taxiway intersection nearest the self-service fuel pumps, from which point about 2,400 ft of runway was available."

Graphic Source: NTSB

The NTSB report continues further yet: "The airport was surrounded by mountainous terrain. The Federal Aviation Administration chart supplement insufficiently described the topography off the departure end of runway 28, as it failed to include any description of the peaks and valleys immediately off the end of the runway nor did it include the presence of a 4,000 foot-tall mountain peak about 1 nm west of the runway end. A witness stated that most airplanes departing the accident airport used runway 10. The terrain off the departure end of runway 10 comprised mostly open farm fields for several miles."

Graphic Source: NTSB

The analysis Section of the NTSB report concludes with this, "The reason for the pilot’s steep turn just after takeoff could not be determined based on the available information. It is possible that he may have been maneuvering due to the rising terrain or attempting to return to the runway due to a perceived problem (the “pop” sound noted by a witness). The angle of descent indicated by impact signatures at the accident site was more consistent with a controlled flight into terrain event than that of an aerodynamic stall and loss of control; therefore, it is likely that the pilot failed to maintain clearance from trees while maneuvering after takeoff. A departure from runway 10 instead of runway 28 would have provided the pilot with more favorable terrain clearance and forced landing sites if the pilot had encountered an anomaly during the takeoff."

Photo Source: NTSB - Engine after Recovery

The NTSB Probable Cause states: "The pilot’s failure to maintain clearance from trees after entering a steep banked turn for unknown reasons. Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s decision to take off toward rising terrain."

Whether the pilot used the full length of the runway or departed from the intersection with the taxiway or whether an engine issue occurred is immaterial to our discussion of risk analysis. Had the pilot looked at the terrain critically, even considering the lack of information in the Chart Supplement, a risk assessment would have clearly indicated a departure on Runway 10 was safer. The weather observation used in the accident report was from a station 40 nm away, it shows that the wind was light. If the wind direction in the report is valid for the accident airport, which is questionable, the pilot would have taken off with a slight tailwind. If the pilot was in a hurry, taking off on Runway 10 would have necessitated a long back-taxi from the intersection near the fuel pumps so that may have influenced his decision to use Runway 28, either full-length or from the intersection.

The lesson here is to always take a pause, think about the "what-ifs" and make a good decision in the interest of safety.

Click here to download the accident report from the NTSB website.

Accidents discussed in this section are presented in the hope that pilots can learn from the misfortune of others and perhaps avoid an accident. It is easy to read an accident report and dismiss the cause as carelessness or as a dumb mistake. But let's remember that the accident pilot did not get up in the morning and say, "Gee, I think I'll go have an accident today." Nearly all pilots believe that they are safe. Honest introspection frequently reveals that on some occasion, we might have traveled down that same accident path.

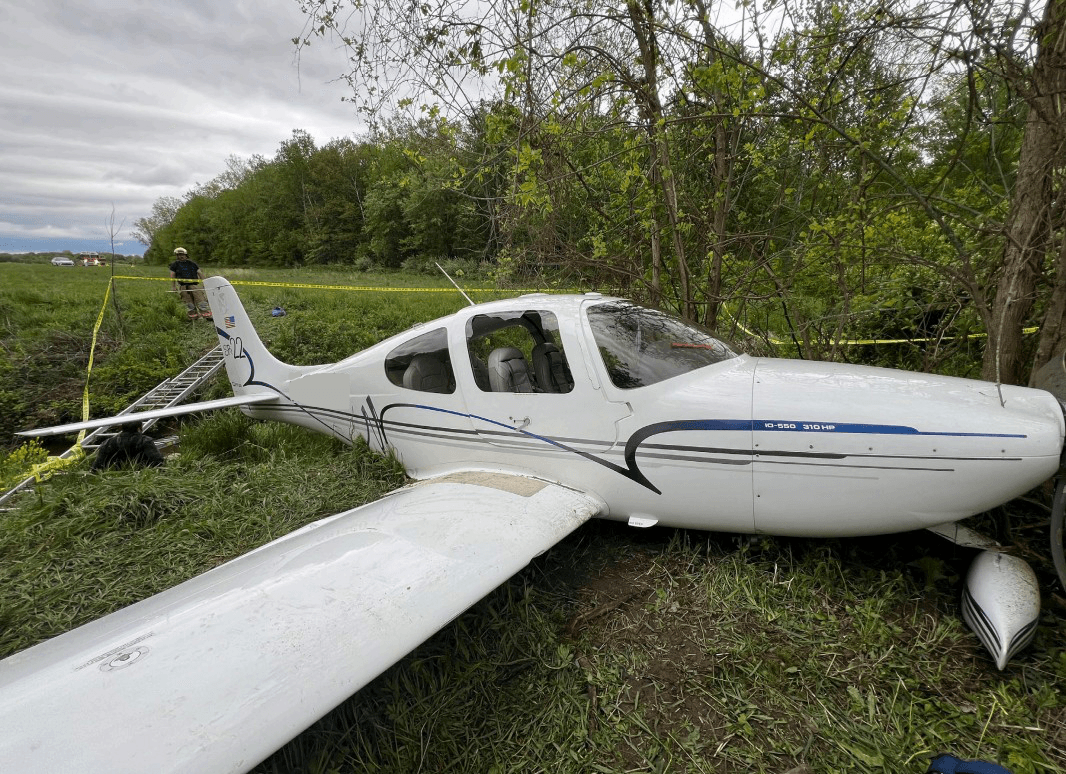

This crash involved an excursion off a wet turf runway. The 52-year-old, 1317 hour private pilot and one passenger were uninjured, but an unrestrained passenger received serious injuries. The airplane was a Cirrus SR22 and the crash happened in Michigan in May 2024.

NTSB Photo

The NTSB report includes the following: "The pilot reported that while landing on a wet turf runway, the airplane began to skid. He initiated a go-around and then determined that he would not be able to clear the trees at the end of the runway. The pilot aborted the go-around and the airplane landed on the remaining runway, continued off the end of the runway, and impacted trees. The airplane came to rest upright on the ground in a grove of trees."

Graphic Source: Google Earth - Howard Nixon Memorial Airport (Annotation by GB)

The NTSB report also includes the following: "During the accident sequence an un-restrained passenger sustained a serious injury, and the airplane sustained substantial damage to the fuselage. The pilot stated that he provided the passenger a briefing on the use of the seatbelts before the accident; however, he did not confirm the passenger was wearing the seatbelts before landing. The passenger had unfastened the seatbelt during the flight."

The NTSB probable cause states: "The pilot’s failure to maintain control while landing on a wet turf runway, which resulted in a runway excursion and impact with trees. Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s failure to ensure the passenger’s proper use of seatbelts before the landing."

This provides a reminder of our duties as pilots to ensure that our passengers are properly secured before flight and during landing.

In the pilot's report to the NTSB, he stated, "I was on an IFR flight plan. I waited until I was 5 Nmiles from airport and had it in sight before canceling my IFR. I flew over the airport first to get a good look at it and make sure I was choosing the correct runway to land. There was no rain and visibility was good, tops at 3000 and I was at 1700. I performed a proper sequence to land and I did land - but when the tires were on the ground I hit the breaks the plane started to skid and actually accelerate not decelerate so I attempted a go around and realized I would not make it over the trees at end of the runway so I again pulled back power in an attempt to slow as much as possible before impact. Thankfully we had just enough speed to make it over the creek at the end of the runway and we were no longer airborne so we impacted at ground height but past the creek bank."

But the big lesson here is the need for a risk assessment for any runway, but a turf runway, possibly wet, should cause us to carefully consider our options before committing to a landing. The runway length is reported to be 2,800 feet. That is ample for the airplane on a dry, hard surface, but wet turf would make the airplane susceptible to skidding if any substantial braking was applied. Doubling the published landing distance for wet turf is a good rule of thumb. Once the airplane is on the runway and begins to skid, the go-around becomes problematic. Energy has been dissipated and runway length has been used up. The pilot did not state how far down the runway he had landed. His statement that he "hit the brakes" may indicate initial hard braking. We cannot know precisely what happened.

A risk analysis should address how to mitigate identified risks. That would, in this case, include making sure the airplane was going to touch down as close as possible to the beginning of the runway and remembering to go lightly on the brakes to avoid locking up the wheels and skidding.

To the pilot's credit, when he realized that he would not clear the trees during the go-around he aborted. Going into the trees while on the ground at relatively low speed is far better than flying into trees at low altitude or stalling the airplane by increasing the angle of attack in an attempt to clear the trees. Had the passenger been properly secured this mishap would have been property damage only.

Click here to download the accident report from the NTSB website.

Accidents discussed in this section are presented in the hope that pilots can learn from the misfortune of others and perhaps avoid an accident. It is easy to read an accident report and dismiss the cause as carelessness or as a dumb mistake. But let's remember that the accident pilot did not get up in the morning and say, "Gee, I think I'll go have an accident today." Nearly all pilots believe that they are safe. Honest introspection frequently reveals that on some occasion, we might have traveled down that same accident path.

This crash took the life of the 73-year-old pilot and his 57-year-old wife. The instrument rated private pilot had 1473 total flight hours, all in this T182T. It occurred in Wyoming in May 2023.

The NTSB report begins: "The pilot and passenger departed the airport on an instrument flight rules (IFR) flight in an airplane that was prohibited from flight into icing conditions and over the maximum takeoff weight. Instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) prevailed and included forecasted moderate icing conditions, mountain obscurations, moderate turbulence, and cloud formations from about 8,300 ft mean sea level (msl) to 18,000 ft. About 30 minutes after departure while enroute at 13,000 ft, the pilot reported mild ice to the air route controller but stated that they were “OK.” The airplane remained on the assigned route and altitude for about the next 17 minutes, when it gradually slowed from its cruise speed by about 20 knots without an indication of a reduction of power. The airplane then turned right, off course, and began to descend from its assigned altitude. Engine data monitor (EDM) data showed that, about that time, the pilot added power above the cruise power setting. The airplane stopped turning but continued heading off course while descending for about 1 mile. The air route controller made multiple altitude alerts and advised the pilot to climb immediately. The pilot only advised the controller that he had a problem. The airplane continued deviating away from the assigned route and descending, while the groundspeed of the airplane varied. The airplane entered a descending, tightening right turn with climb power applied. The airplane remained in the descending, tightening right turn at descent rates of up to 1,825 ft per minute until the last recorded data point at 965 ft above ground level (agl), located about 890 ft north of the accident site."

NTSB Graphic

The NTSB report includes: "The pilot and passenger were returning from a trip that occurred over several days and consisted of multiple flight legs and included weather delays. The day of the accident was to be the final day of the trip. Departing on the flight while moderate icing conditions were forecast, and continuing along the flight route after experiencing ice accretion on an airplane prohibited from operating in icing conditions, are consistent with poor aeronautical decision making. The continuous right turn with a reducing radius suggests that the pilot remained in IMC conditions during the descent and may have experienced spatial disorientation while also reacting to the stall recovery; however, the airplane’s steep impact angle, minimal debris field, and damage signatures were consistent with a stall/spin event when the accident occurred."

NTSB Photo

The NTSB report also states: "According to a certificated instrument flight instructor (CFII), he flew 11 flights with the accident pilot between September 4, 2020, to February 8, 2023. The flights included two instrument proficiency flights that occurred on September 4, 2020, and January 28, 2022. He recorded 16 approaches and logged 15.5 hours of dual flight time including 10.0 hours of hood time. He reported the accident pilot’s instrument flying skills showed remarkable improvement from previous instrument flights. The flight instructor recalled that on the last instrument training flight with the accident pilot, about October 6, 2023, he noticed that the attitude indicator would develop an error and give false indications. He advised the pilot to get the attitude indicator fixed before taking the airplane into instrument conditions. While on the flight, the CFII took a photograph of the instrument panel that showed the attitude indicator and the turn coordinator were not in agreement; the attitude indicator showed the airplane in a left turn while the turn coordinator indicated a right turn."

NTSB Image provided by CFI

NTSB Graphic

The NTSB probable cause states: "The pilot’s decision to conduct flight into an area of icing in an airplane that was prohibited from such conditions, which resulted in exceedance of the airplane’s critical angle of attack, an aerodynamic stall/spin, and the pilot’s spatial disorientation while attempting to recover from the loss of control."

NTSB Photo

This was the final leg of a long flight spread over a couple of days. Did the desire or need to get home influence the pilot's decision to depart? Our blog this month encourages doing a risk analysis. How could departing into forecast moderate icing conditions in an airplane that was prohibited from flying in known icing conditions be consistent with doing an honest risk analysis? The pilot was likely making subjective decisions and our cognitive biases can exert great influence there. And then, at the first sign of structural icing, another risk analysis should have been performed, but the pilot informed ATC that there was some ice, but that he was "okay." Continuation bias was most likely weighing in on the pilot's decision to continue. The airplane will fly with a little ice, but that should be a sign to immediately exit the icing condition by either finding a suitable altitude where ice will no longer form or turning around and flying back out of the icing conditions.

Then we must consider the possible issue with the attitude indicator. The NTSB states that it was destroyed in the crash and could not be examined or tested. The photo supplied by the CFI certainly indicates a problem and there is no record of any repair or replacement being made. If the attitude indicator had failed as the pilot was dealing with more serious icing, the pilot's workload may have exceeded his capabilities resulting in spatial disorientation and loss of control. The pilot had received a substantial amount of instruction on instrument flying in the recent past. It seem likely that some of that would have included practice in partial panel flying.

I would like to raise one other question that was not addressed in the NTSB report. Analysis of the time line indicates that it is likely the pilot had been operating above 10,000 feet for at least 30 minutes and the report does not mention supplemental oxygen. The pilot was 73-years-old and presumably in good health. But, age can be a contributing factor to increased hypoxia susceptibility. Even mild hypoxia, a slight reduction in oxygen delivered to the brain, impairs mental performance by disrupting the brain's energy metabolism and signaling. Perhaps mild hypoxia interfered with the pilot's decision making or his overall mental performance.

We will never know for sure what happened in that airplane or what decisions were made (or not made) in the minutes leading up to the crash.

Click here to download the accident report from the NTSB website.

Not subscribed to Vectors for Safety yet? Click here to subscribe for free!