New Video in Our "Essential Vectors" Series

"Slips Essentials" provides an overview of the essential information a pilot needs regarding forward and side slips. In about 2 ½ minutes, we explain what the slip maneuver is and its practical uses. We explain a common misconception and show an example of what a slip looks like on the turn coordinator. We also add some cautions regarding slips. Click here to view it on YouTube.

Cold Weather Engine Starts

Check out our new article in our "Safety Concepts" section. Click here to see the article.

Is Your Instructor Legal?

A recent article in Flying Magazine details a case in which a CFI had failed a recertification checkride, had his commercial and flight instructor certificates revoked, but continued to instruct for more than a year with the knowledge of the flight school owner. Finally, there was a fatal crash in which the student pilot died but the non-certificated instructor survived. Tragedy aside, the article notes that hours logged by students being instructed by the non-certificated instructor become invalid. Trust by verify. You are within your rights to ask to see your CFI's certificates. Click here to read the article on Flying Magazine's website.

New Edition of "Old Pilot Tips

Episode #36 titled "Be Coordinated" is now available. In under one minute, see a reminder about the importance of maintain coordinated flight and get an example of an easy coordination exercise. Our "Old Pilot Tips" series is sponsored by Avemco Insurance and is narrated by Gene Benson. Click here to watch Episode #36 on YouTube.

Recommended Reading

There are far too many accidents and incidents happening on ramps and during taxi. For a good refresher, click here to read our article, "Ramp and Taxi Safety" on the Vectors website.

Free Virtual Safety Presentations Available

As you plan your late fall and winter meetings for your pilot group, consider including a virtual guest speaker. We can provide a safety presentation, valid for Wings credits if you choose, free of charge, courtesy of Avemco. For more information or to schedule, contact gene@genebenson.com. Click here to download a copy of our current presentation catalog.

Paying Attention

Does this scenario sound vaguely familiar? As 10-yer-old elementary school student, I recall the teacher seeming to be droning on and on with some unimportant facts about a subject in which I had no interest. I was lured to the bright sunshine coming through the window directing my thoughts toward riding my bike to the airport after school let out. Suddenly, I was jolted back to reality when the teacher sternly called out my name followed by an admonition to “PAY ATTENTION!”

The teacher was likely aware that I was not the only student who was not fully engaged in her riveting explanation of adverbs, adjectives, conjunctions and sentence structure. She knew that singling out one student would universally restore focus to her lesson. She was correct, but for how long? The remainder of the lesson? Probably not. Was the class hers for the next ten minutes, two minutes, 30 seconds?

Human attention is a complex subject. Paying attention is a dynamic process engaging several neural circuits, with the prefrontal cortex and related networks filtering and prioritizing incoming information, ultimately shaping what is consciously noticed and acted upon.

Attention also operates at different levels:

- Selective attention allows focusing on one specific stimulus while filtering out others.

- Sustained attention enables maintaining focus over long periods.

- Divided attention manages resources between multiple tasks at once.

- Attentional control involves consciously choosing what to focus on or ignore.

The attention span in individual humans is determined by a combination of neurological, psychological, and environmental factors. Genetic factors influence brain structure and function, contributing to individual differences in attention capacity. Conditions such as ADHD, anxiety, depression, or fatigue can impair attention span. Physical health issues like poor sleep, nutrition, or chronic illness also reduce the ability to maintain focus. Personal interest in a task, motivation, and emotional engagement powerfully affect how long attention is sustained. Tasks perceived as rewarding or meaningful typically hold attention longer. Distractions, noise, multitasking demands, and environmental stressors can shorten attention span. Structured environments that minimize interruptions help maintain focus. Complex or monotonous tasks differently impact attention duration. High cognitive load or unengaging tasks can cause quicker fatigue of attention resources. Attention span is not fixed but a dynamic trait influenced by brain biology, health, motivation, environment, and task context.

Attention span develops and changes through childhood into adulthood and may decline with age. Like other cognitive skills, steps can be taken to at least slow decline or possibly improve attention span with age. Not surprisingly, the cast of characters is the same as for other cognitive skills. We need adequate sleep, good nutrition, aerobic exercise, and brain exercises. Some medications can reduce attention span while others can increase it. Pilots should consult with their AME regarding any medications or supplements.

Being a pilot requires the highest level of attention with our constant need to prioritize items needing our attention and to switch focus rapidly to another task. Yet, our individual abilities to pay attention and to focus are never measured directly. It is our own responsibility to evaluate our ability and to take appropriate steps to identify and treat any issues regarding impaired ability to attend to necessary tasks. We can self-evaluate our ability to pay attention using various methods, though they are not a substitute for a clinical diagnosis. These techniques include standardized questionnaires, focused personal journaling, and timed cognitive tasks.

Paying Better Attention?

Our cognitive science article this month took a shallow dive into the science of human attention. We all know that paying close attention while flying an airplane, whether hand flying or using an autoflight system, is essential. But how many of us really do that? All? Most? A few? The honest answer is that none of us do. We might intend to, try to, think we do, but it is not possible for us mere humans to pay close attention to a flight that lasts more than a few minutes. Regardless of our intent, our attention will be periodically diverted away from flying the airplane. We might shift our attention briefly to an interesting terrain feature below, to a pilot we hear stumbling with an ATC communication, to a need to void that last cup of coffee, to a shoulder harness rubbing annoyingly on our neck, to that disagreement we had with our spouse, to some uncertainty about our employment, or to something else.

We have many things competing for our attention. Our brains do a reasonably good, but not a perfect, job of sorting out all the stimuli competing for our attention. Simply put, some people are better than others at focusing on what is most important at a given time. But that ability is variable. The person who is extremely capable of managing their attention at one point in time may become deficient later. The ability is influenced by many factors which can be subject to rapid change. Fatigue, dehydration, medications, minor illness, and even monotony of a task can negatively impact human attention.

As pilots we can take steps to improve our abilities related to attention by following the same guidelines recommended for maintaining our cognitive ability in general. These are primarily nutrition, aerobic exercise, and brain exercise. Additionally, maintaining and improving proficiency in our flying skills is critical. This can be accomplished by taking instruction or recurring training in the airplane or in a simulator.

All the above is based on the premise that the pilot is responsible and wants to pay attention to all aspects of the flight. Unfortunately, advances in technology have opened the door to an over-reliance on automation for some pilots. We have a few documented cases of this in professional aviation and a few suspected cases in general aviation. Recently, heard on the frequency, was an air traffic controller admonishing an airline crew to, “Put down the iPads and pay attention.” In GA, we have seen a few accidents which suggest that the single pilot was attending to business matters while allowing the autoflight system to conduct the flight.

Flying an airplane is a complex operation requiring all the attention we can provide. Taking steps to improve our attentiveness capability and then devoting our full attention to the flight will make us safer pilots.

Accidents discussed in this section are presented in the hope that pilots can learn from the misfortune of others and perhaps avoid an accident. It is easy to read an accident report and dismiss the cause as carelessness or as a dumb mistake. But let's remember that the accident pilot did not get up in the morning and say, "Gee, I think I'll go have an accident today." Nearly all pilots believe that they are safe. Honest introspection frequently reveals that on some occasion, we might have traveled down that same accident path.

This crash was very high profile in the Western New York State area. A very successful and well know attorney, died in the crash of his Socata TBM 700 in October of 2020. His only passenger, his 32-year-old niece, was also killed in the crash. She was an attorney employed by the federal government. The stated purpose of the flight was for the pilot to take his niece to Buffalo for a birthday party to honor the mother of the pilot and grandmother of the passenger. The pilot had flown from Buffalo to Manchester, New Hampshire earlier in the day and the accident happened on the return leg of that flight.

NTSB Photo - Actual Accident Airplane

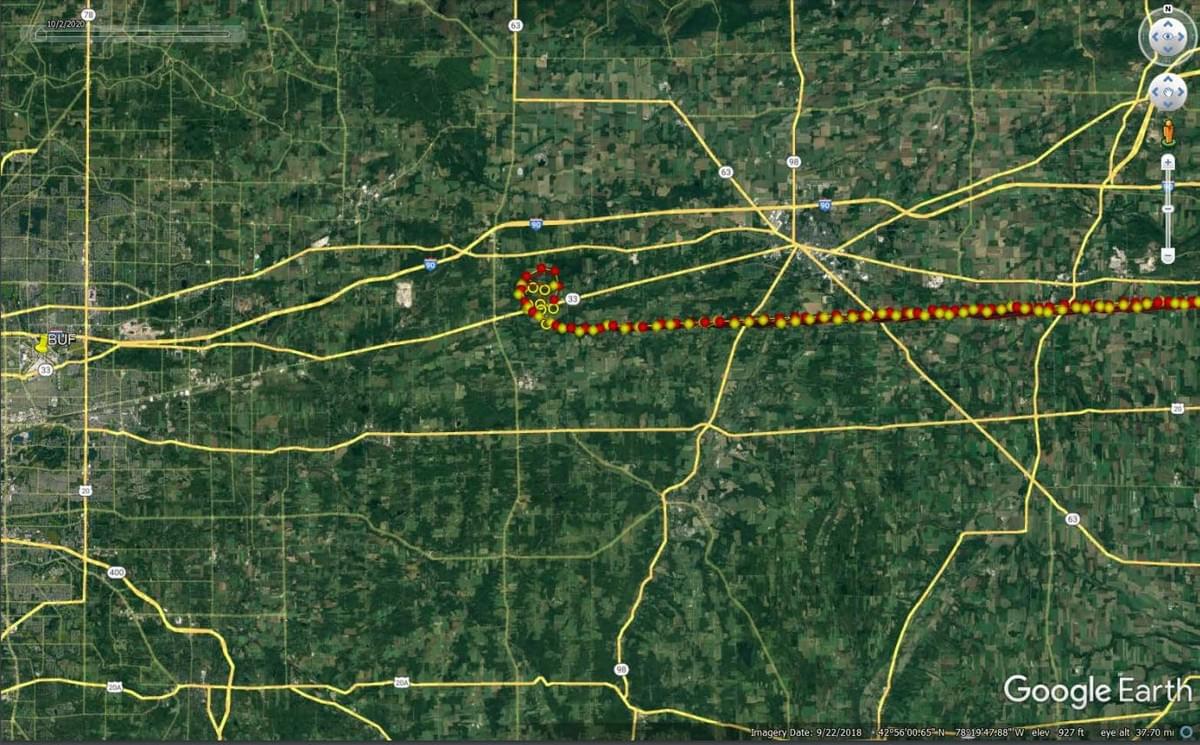

Please bear with me as I present much more of the NTSB accident report than I usually do. I believe it clearly tells the story of the flight. "The airplane was in cruise flight at FL280 when the instrument-rated pilot failed to contact air traffic control (ATC) following a frequency change assignment. After about 25 minutes, and when 30 miles east of the destination airport, the pilot contacted ATC on a frequency other than the one that was assigned. He requested the instrument landing system (ILS) approach at his intended destination, and the controller instructed the pilot to descend to 8,000 ft and to expect vectors for the ILS approach at the destination airport. The controller asked the pilot if everything was “okay,” to which the pilot replied, “yes sir, everything is fine.” The controller then observed the airplane initiate a descent. About 2 minutes later, the controller asked the pilot where he was headed, and the pilot provided a garbled response. The controller instructed the pilot to stop his descent at 10,000 ft, followed by an instruction to stop the descent at any altitude. The pilot did not respond, and additional attempts to contact the pilot were unsuccessful. The airplane impacted terrain in a heavily wooded area 17 miles from the destination airport."

NTSB Graphic

The NTSB report includes the following: "All major components of the airplane were located in the vicinity of the main wreckage. Examination of the airframe and engine revealed no preimpact mechanical malfunctions or failures with the airplane that would have precluded normal operation. The investigation was unable to determine why the pilot was not in contact with ATC for 25 minutes. The pilot’s eventual contact with ATC about 30 miles from his intended destination, while still operating at his cruise altitude, suggests a clear breakdown in awareness of his position through distraction or impairment. However, upon re-establishing contact with ATC, the pilot’s communications were clear, nominal, and timely, which did not suggest impairment or use of an oxygen mask. Additionally, in response to a direct query from ATC the pilot did not indicate any difficulty. Further, there was no sign of airframe depressurization and examination of the wreckage did not reveal deployment of the passenger oxygen masks. Toxicology results were positive for ethanol at a low level, which was likely due to post-mortem production."

The NTSB report also includes: "Meteorological data and a performance study indicated that the pilot initiated a descent through multiple cloud layers about 15 seconds after acknowledging the descent clearance. During the initial portion of the airplane’s descent, its airspeed and rate of descent appeared to be nominal. About 2 minutes later, excessive airspeeds, descent rates, bank angles, and pitch attitudes were achieved. The performance study depicted the airplane entering a spiral dive during which the airplane exceeded airspeed, maneuvering, structural, and autopilot limitations. At 6,000 ft above ground level, and about 10 seconds before ground contact, the airplane descended through a final cloud layer, the descent profile shallowed, and the rate of descent decreased to 6,800 ft/min before radar data ended. In addition, there were no clearances issued by ATC that would have required the pilot to change either the airplane’s rate of descent or track about this time; however, the airplane’s proximity to the destination airport may have created a heightened sense of urgency for the pilot to descend and or configure his avionics for the approach, which may have served as an operational distraction. Although it was possible that restrictions to visibility during the descent may have affected the pilot’s ability to maintain positive airplane control, there is insufficient information to determine how or why the pilot lost control. Meteorological data and a performance study indicated that the pilot initiated a descent through multiple cloud layers about 15 seconds after acknowledging the descent clearance. During the initial portion of the airplane’s descent, its airspeed and rate of descent appeared to be nominal. About 2 minutes later, excessive airspeeds, descent rates, bank angles, and pitch attitudes were achieved. The performance study depicted the airplane entering a spiral dive during which the airplane exceeded airspeed, maneuvering, structural, and autopilot limitations. At 6,000 ft above ground level, and about 10 seconds before ground contact, the airplane descended through a final cloud layer, the descent profile shallowed, and the rate of descent decreased to 6,800 ft/min before radar data ended. In addition, there were no clearances issued by ATC that would have required the pilot to change either the airplane’s rate of descent or track about this time; however, the airplane’s proximity to the destination airport may have created a heightened sense of urgency for the pilot to descend and or configure his avionics for the approach, which may have served as an operational distraction. Although it was possible that restrictions to visibility during the descent may have affected the pilot’s ability to maintain positive airplane control, there is insufficient information to determine how or why the pilot lost control."

NTSB Photo: Wing Spar

The NTSB probable cause finding states, "The pilot’s failure to maintain control of the airplane for undetermined reasons during the descent to the destination airport."

The pilot had purchased the airplane in 2016. At the time of the accident, he was age 62, instrument rated private pilot, had a current Class 3 Aviation Medical Certificate, and had completed a recurrent training course on the TBM at SIMCOM about 8 months prior to the accident. According to the NTSB report, he had about 960 hours total flight time including about 239 hours in the TBM.

What could account for a 25-minute period of no contact with ATC? Was the pilot simply not paying attention? We cannot know, but we must raise the possibility that the pilot got deeply involved in conversation with his passenger, also an attorney and, with the autopilot flying the airplane, began discussing legal business and perhaps looking at documents or contracts. This scenario for the TBM crash would include the pilot, suddenly realizing the situation, disconnecting the autopilot to hand fly the instructions provided by ATC, and suffering from spatial disorientation while attempting to make a turning descent. The description of the descent provided in the accident report is characteristic of a loss-of-control due to spatial disorientation. Of course, all of this is purely speculation on my part.

The possibility of hypoxia given the 28,000 feet cruising altitude has been raised. I see no evidence to support that theory. The airplane has multiple warning systems to warn of increasing cabin altitude, the passenger oxygen masks had not been deployed per the automatic system, and the pilot's voice on the final ATC recording did not sound like a pilot recently recovered from hypoxia.

Lesson to be learned: Always be attentive to the flight. Monitor the track and ATC closely when using the autopilot.

Accidents discussed in this section are presented in the hope that pilots can learn from the misfortune of others and perhaps avoid an accident. It is easy to read an accident report and dismiss the cause as carelessness or as a dumb mistake. But let's remember that the accident pilot did not get up in the morning and say, "Gee, I think I'll go have an accident today." Nearly all pilots believe that they are safe. Honest introspection frequently reveals that on some occasion, we might have traveled down that same accident path.

The 80-year-old, 4506-hour commercial pilot died in the crash of a Cessna 414 in California. The crash occurred on January, 18, 2023. The NTSB report begins, "Shortly after taking off, the pilot was instructed to change from the airport tower frequency to the departure control frequency. Numerous radio transmissions followed between tower personnel and the pilot that indicated the airplane’s radio was operating normally on the tower frequency, but the pilot could not change frequencies to departure control as directed. The pilot subsequently requested and received approval to return to the departure airport. During the flight back to the airport, the pilot made radio transmissions that indicated he continued to troubleshoot the radio problems."

NTSB Photo

The NTSB report continues: "The airplane’s flight track showed the pilot flew directly toward the runway aimpoint about 1,000 ft from, and perpendicular to, the runway during the left base turn to final and allowed the airplane to descend as low as 200 ft pressure altitude (PA). The pilot then made a right turn about .5 miles from the runway followed by a left turn towards the runway. A pilot witness near the accident location observed the airplane maneuvering and predicted the airplane was going to stall. The airplane’s airspeed decreased to about 53 knots (kts) during the left turn and video showed the airplane’s bank angle increased before the airplane aerodynamically stalled and impacted terrain."

NTSB Photo

The NTSB report also includes the following: "The accident is consistent with the pilot becoming distracted by the reported non-critical radio anomaly and turning base leg of the traffic pattern too early during his return to the airport. The pilot then failed to maintain adequate airspeed and proper bank angle while maneuvering from base leg to final approach, resulting in an aerodynamic stall and impact with terrain."

NTSB Photo

The NTSB probable cause states "The pilot’s exceedance of the airplane’s critical angle of attack and failure to maintain proper airspeed during a turn to final, resulting in an aerodynamic stall and subsequent impact with terrain. Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s distraction due to a non-critical radio anomaly."

NTSB Video (Click the image to run.)

The NTSB accident docket includes a witness statement. The witness, and aviation maintenance technician, interacted with the pilot on the morning of crash, when the pilot was picking up his airplane. The witness stated that the pilot seemed befuddled and somewhat nervous however he also said this was his normal demeanor. He said the pilot didn't fly very much and he thought he had had previous airplane accidents. The same witness added that he often needed to talk up a little louder during normal conversation with the pilot.

The toxicology testing on the pilot revealed the presence of diphenhydramine, a sedating antihistamine, in his liver and muscle tissue. The NTSB report stated that: "While therapeutic levels could not be determined, side effects such as diminished psychomotor performance from his use of diphenhydramine were not evident from operational evidence. Thus, the effects of the pilot’s use of diphenhydramine was not a factor in this accident." I do not often question NTSB findings, but without a determination of the levels of the drug, to rule out this highly impairing substance that both the FAA and NTSB have recommended not flying for a minimum of sixty hours after a final dose, seems odd.

Actual Accident Airplane - Bureau of Aircraft Accident Archives

Our theme this month is being attentive to our flight. Multiple items can work together to interfere with our ability to focus and pay attention to the most important tasks at a given moment. The NTSB blames the crash on the pilot stalling the airplane. They added that contributing to the accident was the pilot’s distraction due to a non-critical radio anomaly. From a human factors perspective, the radio anomaly was likely just one of several factors degrading the pilot's ability to attend to the basic task of flying the airplane. The pilot had not flown much recently, and this was a very complex airplane so proficiency may have been diminished. The witness stated that the pilot seemed "befuddled and nervous." That alone could be evidence that the pilot was not up to the task of flying this airplane on this day.

Regardless of whatever factors were in play on that January day in 2023, our lesson is that we need to be cognizant of our capabilities. If we cannot rise to meet the tasks that may be presented to us, we need to stay on the ground. I have recently written about not taking problems airborne and that applies to our physiological and psychological problems as well as to our airplane's mechanical problems.

Click here to download the accident report from the NTSB website.

Accidents discussed in this section are presented in the hope that pilots can learn from the misfortune of others and perhaps avoid an accident. It is easy to read an accident report and dismiss the cause as carelessness or as a dumb mistake. But let's remember that the accident pilot did not get up in the morning and say, "Gee, I think I'll go have an accident today." Nearly all pilots believe that they are safe. Honest introspection frequently reveals that on some occasion, we might have traveled down that same accident path.

This crash happened in Chattanooga, Tennessee in July of 2023. The 79-year-old pilot and the 80-year-old flight instructor were seriously injured and the airplane was substantially damaged. the NTSB report includes the following: "The pilot and the flight instructor were climbing out after departing from the airport when the cabin door suddenly opened. The flight instructor tried to close the door but could not get it closed properly. The pilot subsequently returned to the airport to land. During the landing approach, the pilot was distracted, flew too low, and the airplane contacted several approach lights short of the runway threshold. The airplane sustained substantial damage to the wings and empennage."

NTSB Photo

The NTSB Form 6120 submitted by the pilot includes the following: "Hit approach lights I'm told clipped airport boundary fence, touched down on gear then Impacted gravel burm [sic] which sheared landing gear and opened fuel tanks. Plane came to rest with approach light impacted in right wing." The pilot also reported that seven approach lights were impacted and destroyed.

NTSB Photo

The NTSB probable cause states: "The pilot’s failure to maintain the proper glidepath during final approach, which resulted in a collision with the approach lights short of the runway. Contributing was the pilot’s distraction due to the cabin door opening."

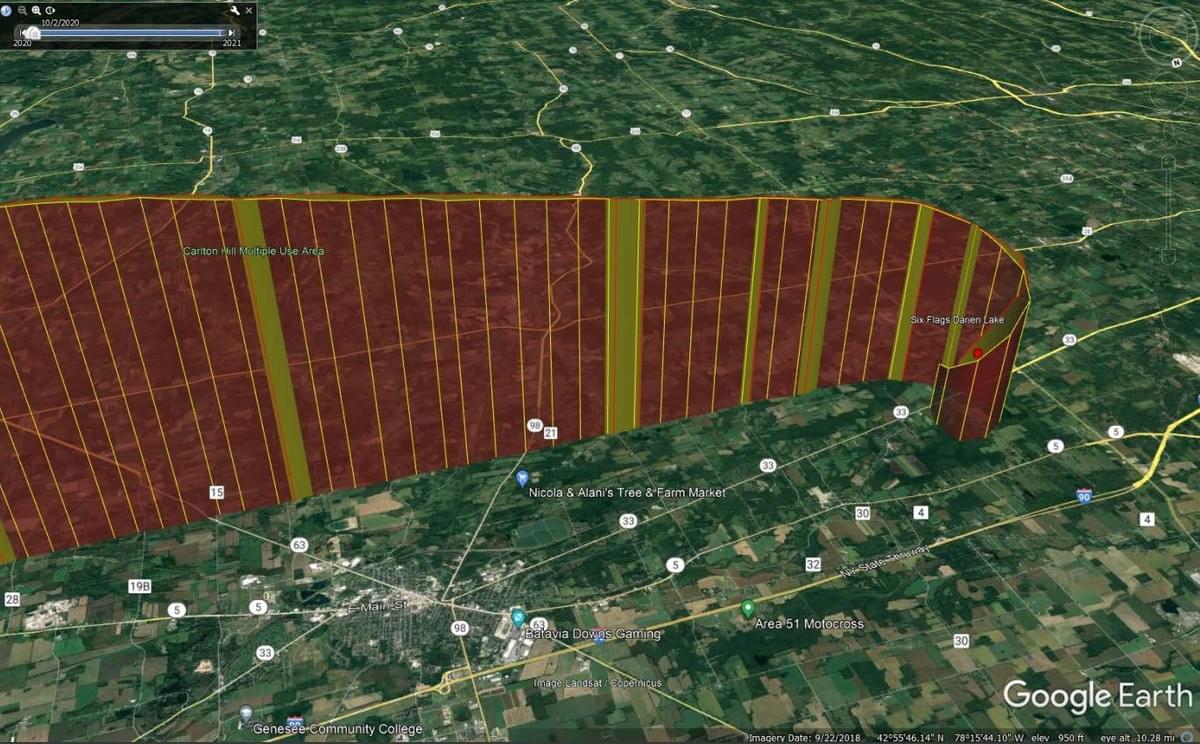

Approach End of Runway 20 at KCHA (Google Earth)

Obviously, neither the pilot nor the CFI were paying attention to the approach path while on short final. We see many accidents and incidents in which a distraction took the pilot's focus away from a critical task. In this case, the door had been unlatched since shortly after takeoff so there was no immediate reason for it to be a distraction. We must frequently remind ourselves that our most important task is to fly the airplane regardless of what distractors might be at work.

Click here to download the accident report from the NTSB website.

Not subscribed to Vectors for Safety yet? Click here to subscribe for free!

Looking for a holiday gift for a pilot? Check out my publications on Amazon. "Fifty Years of Flying Insights" is available in Paperback, Kindle, or Audio books. The three editions of "Thoughts on Being a Better, Safer Pilot" are available as Kindle or Audio books. Click the image above to visit my Author Page on Amazon.